-

There are no right or wrong answers when interpreting poetry or prose.

As a new teacher, I was guilty of reinforcing this misconception with students; I wanted my students to feel comfortable and confident in expressing their thoughts. I quickly changed my approach when a student wrote an essay explaining that Macbeth really took place within a dream realm, and the title character never really experienced any of the events of the play. This student referenced other works (mainly television shows) that used this plot twist as support.

While interpretation is somewhat subjective, of course there are wrong answers! Creativity or innovation that is not deeply rooted in relevant sources of support is meaningless to interpretation. English course writers must provide abundant support to teach students how to interpret literature, including how to make strong and logical inferences as well as how to support those inferences from the text or relevant outside sources. Course writers must address these issues within the curriculum by including instruction and practice for students to identify relevant sources, utilize textual evidence to reinforce claims, and critique their own interpretations for flaws or inconsistencies. Likewise, when writers develop answer keys for short-answer or essay questions, they should provide the teacher with example answers or key points to look for within students’ responses instead of the ubiquitous phrase “answers may vary.”

-

No one uses literature in the real world.

Students love to ask, “When will I ever use this?” when they are frustrated, struggling, or bored with the material and, at first blush, this might seem like a tough question to answer. Course writers should preemptively address this concern by providing real-life examples of how the study of literature can improve students’ lives in the real world. The most obvious answer is that we study literature to understand human nature: to appreciate others’ experiences, examine our personal beliefs, and consider ethical situations. But we use lessons from literature in much more subtle ways, too. Studying literature improves our critical thinking skills by asking us to take the time and brainpower to really consider an issue. Instead of making quick, thoughtless decisions, literature encourages students to make careful considerations about the information they receive. Course writers can strengthen the subtle applications of literature by tying in critical thinking skills within ELA curriculum.

-

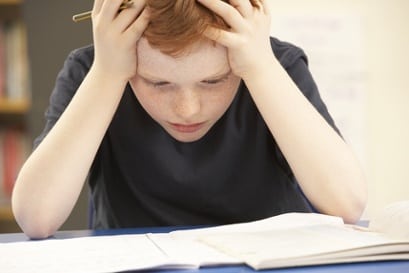

Some people are just bad at reading.

Or some people are just bad at writing, or public speaking, or understanding poetry. While every learner has innate talents and struggles, sometimes students believe there will be some things they just won’t ever be able to master. The truth is that students can always improve and learn new skills, even if they don’t seem to come naturally. All of the skills just listed are learned tasks, and even the best student has something to learn and ways to improve. English curriculum should promote the idea that these skills can be learned, even if they don’t come easily or naturally. Course writers can focus instruction and performance tasks on strengthening basic skills, developing new strategies, and providing opportunities for students to practice their skills. By reinforcing the basic skills while including practice, both struggling and high-performing students can make learning gains and build a strong ELA skill set.

-

The longer the answer, the better.

It’s easy to see how students develop this misconception—English teachers often give students minimum-length requirements for short-answer and essay questions in an effort to encourage well-developed, thoughtful answers. But students may come to the conclusion that if the teacher is expecting one paragraph, three or four will be more impressive…right? English course developers can combat this misconception by emphasizing quality over quantity. They can incorporate instruction in cutting unnecessary words, using potent vocabulary, and providing examples of brief and effective prose and poetry. By incorporating strategies for creating succinct and powerful messages, course developers can help emerging writers become powerful communicators. There are many interactive ways to encourage succinct writing; one fun method is a journalism trick called the stoplight game. Students are directed, “If you only had the length of a stoplight to tell someone as much important information as possible about the story (or essay, paragraph, etc.), what would you say?” Students can do this alone or with partners to see if their responses have useless information or can be reworded for the most clarity and impact in the fewest possible words.

These are just four student misconceptions ELA course writers should address. What are some other common misconceptions, and how do we combat them?